All the ways Javascript ends up in your server

2025-08-06

"'In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people angry and been widely regarded as a Dick move'- Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy"

PS : this is for people who asked me why js is the way it is

a deep dive into all of js.

The History of Javascript on the Client

Picture this: It's 1995. The web is a graveyard of static pages—lifeless text and images that never change, never respond. You click a link, wait for a new page to load. That's it. No animations, no real-time anything.

Then Brendan Eich, A netscape engineer and language designer, gets handed an impossible task: create a programming language for the web. In ten days. Ten days. What should have been months of careful design became a frantic sprint that would accidentally reshape the entire internet.

Javascript wasn't supposed to conquer the world. It was supposed to add simple interactions—maybe validate a form, change some text. But something strange happened. Developers discovered they could do more with this scrappy little language than anyone imagined.

Fast-forward to the early 2000s, and Javascript had become the invisible engine powering every website you visited. What started as a quick hack had evolved into the foundation of the modern web.

The Creator of StackOverflow  Jeff Atwood has a great quote about Javascript:

Jeff Atwood has a great quote about Javascript:

“Anything that can be written in JavaScript, will eventually be written in JavaScript.” - Atwood's law

Have you ever seen a fire spread across a forest? It starts small , everytime ... maybe a couple of feet. But it grows and grows, and eventually it becomes a forest fire. That's what happens when you have a language accessible to everyone, it spreads like a wildfire , burning through complexity and ending up on systems that are not designed to handle it, like the web.

A phenomenon like this was only seen once... by a single other program that predates javascript. you know it and love it....

Atwood's Law became a self-fulfilling prophecy. this was the case in 2000s as well. Just like doom , people found ways to embed javascript in their systems, and it became the norm. Inventions like the browser, the DOM, and the event system were all born out of the need to interact with the web.

Some major innovations in the javascript land was the introduction to the [EVENT LOOP] .

the event loop is an interesting topic of debate , my favourite interview question to ask or be asked is simply

console.log("ONE!");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("TWO!");

}, 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("THREE!");

});

queueMicrotask(() => {

console.log("FOUR!");

});

(async () => {

console.log("FIVE!");

})();

console.log("SIX!");

// Result ->

// ONE!

// FIVE!

// SIX!

// THREE!

// FOUR!

// TWO!

*Question and Solution by Lydia Hallie

The event loop truly made javascript Asynchronous and non-blocking , handling all the concurrent requests and responses in a single thread.

This is a very important concept to understand, and it's the reason why javascript is so fast and performant. and some people did , which brings us to Node.js.

Node.js and the beginning of Javascript on your backend

Ryan Dahl was a math research student in Upstate New York, tinkering away in 2009 on a project that would change the web forever: [Node.js]. At the time, the idea of running JavaScript

outside the browser—on the server—was almost unthinkable. Ryan didn’t even set out to use JavaScript at first. But as he explored the possibilities, he realized that JavaScript, powered by Google’s lightning-fast

V8 engine, was uniquely suited for building non-blocking, asynchronous servers. The event-driven model, which had already made JavaScript so powerful in the browser, could be harnessed to handle thousands

of concurrent connections on the backend, all within a single thread.

Ryan Dahl was a math research student in Upstate New York, tinkering away in 2009 on a project that would change the web forever: [Node.js]. At the time, the idea of running JavaScript

outside the browser—on the server—was almost unthinkable. Ryan didn’t even set out to use JavaScript at first. But as he explored the possibilities, he realized that JavaScript, powered by Google’s lightning-fast

V8 engine, was uniquely suited for building non-blocking, asynchronous servers. The event-driven model, which had already made JavaScript so powerful in the browser, could be harnessed to handle thousands

of concurrent connections on the backend, all within a single thread.

This is a good moment to pause and ask: why did JavaScript become so popular on the backend? Sure, it’s convenient to use the same language on both the client and the server, but there’s more to it. Traditional server languages like Java, PHP, or Ruby typically spin up a new thread for every incoming request, which can quickly exhaust system resources and limit scalability. Node.js, by contrast, uses an event loop and a callback-based model to handle I/O operations asynchronously. This means it can juggle many connections at once, without blocking the main thread or spawning a horde of new ones. Suddenly, building scalable, real-time web applications became much more accessible.

Of course, the early days of Node.js weren’t all smooth sailing. There were major hurdles—especially around cross-platform compatibility (Windows support was a pain), and there was no package manager or build tooling to speak of. But the community rallied. Isaac Z. Schlueter stepped up and created [NPM], which quickly became the de facto package manager for Node, making it easy to share and reuse code. Under the hood, [libuv] was a game-changer: it abstracted away the differences between operating systems, providing a consistent, high-performance asynchronous I/O layer for Node on Windows, macOS, and Linux. [node-gyp] made it possible to build native add-ons, further extending Node’s reach.

With these foundations in place, Node.js exploded in popularity. It was revolutionary: suddenly, JavaScript wasn’t just for the browser—it was everywhere. But as with any revolution, new challenges emerged. If Node.js was to be the backbone of modern backends, it needed more than just raw speed and non-blocking I/O. It needed developer-friendly tools and frameworks.

There were problems in the initial days , in particular there were compatibility issues with asynchronousity in windows , there were no package managers and no build tools, but there was hope for the future. People like Isaac Z. Schlueter made [NPM], the package manager for node.

Tools like [libuv] and [node-gyp] helped solve the compatibility issues and made it possible to build native modules for node. libuv in particular was a game changer, it allowed node to use the native asynchronous system calls that were faster and more efficient on every platform! windows, mac and linux.

Node.js was born , grew like a weed and became the most popular server runtime for javascript. This was revolutionary back then, but there were problems , that needed to be solved. If Node could serve as a foundation for backend, does it have the right tools to build a modern backend?

sure there were tools like [Express] and [Koa] , but they were the right tools for the job.

the syntax was easy to learn , and now is deeply ingrained in the language.

const express = require('express')

const app = express()

const port = 3000

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send('Hello Express!')

})

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`Example app listening on port ${port}`)

})

Express allowed you to write a server that was not only fast but also scalable, but it was not a good fit for a backend, People found it easy to extend express with their frontend as well , they statically hosted their frontend in express ( a practice that stretches till this very day with React SSG on express).

// server.js

const express = require("express");

const path = require("path");

const app = express();

const port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

const REACT_BUILD_DIRECTORY = "dist";

// --- Middleware to serve static files ---

// This tells Express to serve all static files (like your index.html, JS, CSS, images)

// from the specified directory.

app.use(express.static(path.join(__dirname, REACT_BUILD_DIRECTORY)));

app.get("*", (req, res) => {

res.sendFile(path.join(__dirname, REACT_BUILD_DIRECTORY, "index.html"));

});

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`Express server running on port ${port}`);

console.log(`Serving static files from: ${path.join(__dirname, REACT_BUILD_DIRECTORY)}`);

console.log("Make sure your React app is built into this directory.");

});

There were a lot other improvements in the ecosystem as well, like [TypeScript] , which is a superset of Javascript that allows you to write typesafe code, which helps you catch errors before they happen , know all the properties of an object before you use them and so on.

const user = {

firstName: "Angela",

lastName: "Davis",

role: "Professor",

};

console.log(user.pincode); // undefined , you will never know

// typescript

const user = {

firstName: "Angela",

lastName: "Davis",

role: "Professor",

}

console.log(user.name)

// Property 'name' does not exist on type

// '{ firstName: string; lastName: string; role: string; }'.

and [Jest] , which is a testing framework that allows you to test your code in a synchronous way. to demonstrate the power of Jest, let's write a test for our sum function.

// sum.js

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

module.exports = sum;

// sum.test.js

import

const sum = require('./sum');

test('adds 1 + 2 to equal 3', () => {

expect(sum(1, 2)).toBe(3);

});

// package.json

{

"scripts": {

"test": "jest"

}

}

Javascript on the server was now capable as ever... it was growing. We had phases like No-SQL , GraphQL , and the rise of the serverless world, where you could build applications that were not bound to a server, but instead were executed on random computers anywhere across the world to provide a better developer experience. concepts of a server and client started to blur, and the new web started to take shape.

Guerillimo Rauch invented a new way of thinking , server side rendering an application. The idea of using react , a client side library to render ui on the server once , then push the javascript to hydrate the client

later on.

// app/page.tsx (App Router in Next 15)

export default async function HomePage() {

// server time actually :)

const time = new Date().toISOString();

return (

<main>

<h1>Hello from Next.js 15 SSR!</h1>

<p>Server time: {time}</p>

<button onClick={() => alert("Hydrated!")}>Click me</button>

</main>

);

}

What the Server Sends (Initial HTML), is very interesting ... when you make a request to https://localhost:3000/ Next.js 15 server renders the React component into HTML and streams it to the browser.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charSet="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<title>Home</title>

<link rel="preload" as="script" href="/_next/static/chunks/main.js">

<link rel="preload" as="script" href="/_next/static/chunks/app/page.js">

</head>

<body>

<div id="__next">

<main>

<h1>Hello from Next.js 15 SSR!</h1>

<p>Server time: 2025-08-31T15:45:20.123Z</p>

<button>Click me</button>

</main>

</div>

<!-- Next.js hydration scripts -->

<script src="/_next/static/chunks/webpack.js" defer></script>

<script src="/_next/static/chunks/main.js" defer></script>

<script src="/_next/static/chunks/app/page.js" defer></script>

</body>

</html>

The HTML already contains the h1 + time, so the page is readable immediately. The button has no event handlers yet it’s static HTML at this point.

Once the JavaScript bundles load, React hydrates the HTML. That means it, Scans the existing DOM (#__next div).Attaches React event listeners (e.g., onClick for the button).Turns the static page into a live React app.

After hydration, clicking the button works, because React attached the handler defined in the component. The idea was soo productive, that many other framework authors took notice of it and started to implement it in their own frameworks. like [Svelte] , [Solid], [Nuxt].

There was still a new improvement to be made in this space , and the final topic of uis is streaming, streaming changed the way we think about SSR, the idea being , what if we could progessively ship html to the browser , instead of waiting for the page to server render completely. what if , we could await for some data later on ... and then fill up the html with that data ?... that turned some gears in the right direction.

// app/page.tsx (Next.js 15, App Router, React 19)

async function getData() {

// simulate slow fetch

await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 2000));

return "This data came from the server!";

}

export default async function Page() {

const data = await getData();

return (

<main>

<h1>Hello from Next.js 15 Streaming SSR!</h1>

<p>{data}</p>

</main>

);

}

Here, getData() delays for 2s → which demonstrates React’s async rendering and streaming.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charSet="utf-8"/>

<title>Home</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="__next">

<main>

<h1>Hello from Next.js 15 Streaming SSR!</h1>

<p>

<!-- React leaves a placeholder here -->

<template id="P:0"></template>

The browser can already show the H1 immediately, even before the async data arrives.

</p>

</main>

</div>

<script>

// React streaming inline data

(self.__next_f=self.__next_f||[]).push([0,"This data came from the server!"]);

</script>

</body>

</html>

More about rendering strategies

Now that we have seen how streaming works, let's talk about the different strategies that emerged from this evolution of JavaScript on the server. Each approach represents a different way of thinking about when and where to execute your JavaScript:

| Strategy | When JavaScript Runs | Use Case | Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSR | Server renders React components on each request, then hydrates on client | Perfect for dynamic content, real-time data, and SEO-critical pages... this is what Nextjs was built for | ⚛️ Next.js, 🟢 Nuxt, 🟠 SvelteKit, 🎯 Remix, 🔷 SolidStart |

| SSG | JavaScript runs at build time to pre-generate static HTML files | Ideal for blogs, documentation, marketing pages that rarely change, like this page right here :D | ⚛️ Next.js, 🟢 Nuxt, 🟠 SvelteKit, 🚀 Astro, ⚡ Gatsby, 📚 VitePress |

| ISR | Build-time generation + on-demand revalidation when data changes | E-commerce product pages, news sites - fast static with fresh data updates | ⚛️ Next.js (pioneer), 🟢 Nuxt, 🟠 SvelteKit |

| CSR | Client-side rendering - JavaScript runs entirely in the browser | SPAs, dashboards, admin panels where SEO isn't critical | ⚛️ React, 🟢 Vue, 🟠 Svelte, 🔴 Angular, 🎨 HTMX + Alpine.js |

| Streaming | Server streams HTML progressively as components finish rendering | Large pages with slow data fetches - show content as it becomes available | ⚛️ Next.js (App Router), 🎯 Remix, 🟠 SvelteKit, 🔷 SolidStart |

| Resumability | Server serializes component state, client resumes from exact point | Qwik's approach - instant hydration without re-executing server work | ⚡ Qwik (exclusive), 🏙️ Qwik City |

| Islands | Interactive islands hydrate independently on static HTML pages | Astro, Fresh - mostly static sites with selective interactivity | 🚀 Astro (pioneer), 🦕 Fresh, 🎨 Marko, 🔮 Enso |

| SSI | Server inserts dynamic content into static HTML using server directives | Great for adding dynamic headers/footers to otherwise static content | 🟢 Nginx, 🔴 Apache, ☁️ Cloudflare Workers, 🎨 HTMX |

| SSR + SSG | Hybrid: Static pages for content, SSR for dynamic user-specific pages | E-commerce sites: static product pages + dynamic user dashboards | ⚛️ Next.js, 🟢 Nuxt, 🟠 SvelteKit, 🎯 Remix |

Note that these are the strategies that come off the top of my mind , there can be many other , but that's just to mention where javascript actually runs, nothing else.

later helped build [Convex], but the interesting part is not "yet another backend service"—it is the shape of the interface. Instead of "here is your SQL endpoint, good luck", the unit you think in becomes: a typed function that returns live data into your React tree. You write something that looks like a plain TypeScript function, and it behaves like a tiny standard: strongly-consistent, reactive, cache-aware by default.

type Message = { id: string; body: string };

const messages = useLiveQuery<Message[]>("messages.list");

// you call a typed function from React

// and the tree re-renders whenever the data shifts

Seen that way, Convex is just one expression of a bigger drift in JS land. The old standard was: "real" backends live in SQL + REST + imperative glue, and the frontend begs for JSON over HTTP. The new standard is: data and UI are allowed to share a vocabulary (types, hooks, streaming), and SQL is demoted to an implementation detail behind that contract. You can see the same thing elsewhere: auth stacks shifting away from framework plugins like next-auth toward protocol-first, typed systems; observability moving from "ship logs into an OTEL collector" to effect systems like Effects where tracing, retries and metrics are values in your type system. It is also jarring: you have to think in types, effects, protocols and "live" data, not just rows and handlers, and plenty of people hate this direction or do not buy that it is "simpler". That disagreement is part of the story too: standards do not flip overnight, they get pulled forward by weird tools, resisted by most people, and only later feel "obvious" in hindsight.

Before we move on, here's some required reading for the "just use the platform" vs "maybe we need more" fight:

- [motherfuckingwebsite.com]

- [bettermotherfuckingwebsite.com]

- [thebestmotherfucking.website]

- [justfuckingusehtml.com]

- [justfuckingusereact.com]

- [justfuckingusehttp.com]

They are all arguing about the same thing from different angles: should the standard be "bare HTML/CSS/HTTP", or is it okay that our day-to-day standard is React, typed backends, effects, streaming, and a stack of abstractions on top?

Now , your simple mind will look at this and be like :

Part of the answer is: even "pure" HTML is not as simple as we pretend. Structure and whitespace change meaning:

The browser's parser, block/inline layout rules and default CSS already bake in a ton of invisible standards you are "using" whether you like it or not. Modern JS tools are basically us admitting that we want to surface and control those rules—about layout, data, auth, effects—in code and types, instead of pretending they do not exist.

Jake Archibaldwrote a whole essay about how even something as tiny as

Jake Archibaldwrote a whole essay about how even something as tiny as /> is a standards war in disguise. In HTML, <br> and <br /> behave the same, but <div /> does not self-close the way it would in XML, and things get even weirder once you embed SVG and the parser switches into "foreign content" mode where /> suddenly matters again. His point is the same as ours: a lot of what we think of as "simple markup" is really a pile of historical compromises and hidden rules; moving standards into code (and sometimes into TypeScript) is mostly us trying to make those rules explicit instead of magical.

Jake loves another version of this trick:

<br />

This text is outside the br.

<br />

This text is also outside the br.

<div />

This text is inside the div. wtf is this?

equivalent to : <div>this text is inside the div. wtf is this?</div>

Thinking about enforcing web standards in the frontend is a good idea, but it's not a silver bullet. There are still many edge cases and quirks that need to be addressed. For example, the <br> tag is not supported in all browsers, and the <div> tag is not self-closing in XML. To ensure consistent behavior across different browsers, you can use the lite-html package, which provides a lightweight wrapper around the native DOM APIs.

But that is a bandage , not the solution . We ship soo much javascript that we need specific mechanisms to handle all the edge cases , buid polyfills and shims for the browser , build type systems , minification , uglification , and more.

Something not a mere mortal could not keep up with , and that is the web. so we built something to help us ship javascript faster and more efficiently.

Let's talk about Bundlers now :)

Let's revisit why we need bundlers, and how they work.

What is a bundler?

A bundler is a tool that takes your code and transforms it into a format that can be loaded by the browser. It does this by analyzing your code, detecting dependencies, and bundling them together in a way that is optimized for the browser.

what does that mean?

it means that you are no longer limited by the amount of javascript , you can bundle all your javascript into a single file, and it will work just fine. the bundler handles all the complexities of loading and executing your code, making it easier to manage and optimize your application.

let's look at an example:

// index.js

import { add } from "./math.js";

console.log(add(2, 3));

//math.js

export function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

in this example, we have two files: index.js and math.js. the index.js file imports the add function from math.js and logs the result to the console. the math.js file exports a function called add that takes two arguments and returns their sum.

when we run this code, the bundler will analyze the code and determine that math.js is a dependency of index.js. it will then bundle both files together into a single file, which can be loaded by the browser.

the bundler will also handle any dependencies that are not yet bundled, and will recursively bundle them as well. this ensures that your code is optimized and efficient, even when it contains complex dependencies.

soo it will look like this :

// bundle.js

(function() {

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

console.log(add(2, 3));

})();

this is a simple example, but it demonstrates the power of bundling. you can bundle your entire application into a single file, and it will work just fine. this is the beauty of bundlers.

How does it work?

The bundler works by analyzing your code and detecting dependencies. it does this by parsing your code and looking for import and export statements. it then creates a dependency graph, where each node represents a file and each edge represents a dependency between two files.

once the dependency graph is created, the bundler starts to bundle the files. it starts with the entry point, which is the file that is being executed. it then recursively traverses the dependency graph, starting from the entry point and bundling each file as it encounters it.

the bundler also handles the loading and execution of the bundled code. it uses a module loader to load the bundled code into the browser's memory. when a module is loaded, the bundler resolves any dependencies and executes the code. this ensures that the code is optimized and efficient, even when it contains complex dependencies.

let's take a few more examples to understand how bundlers work.how does it strip down typescript code ?

// index.ts

import { calculate } from "./utils.ts";

import type { Config } from "./types.ts";

import { logger } from "./logger.ts";

const config: Config = { debug: true };

const result = calculate(10, 5);

logger.info(`Result: ${result}`);

// utils.ts

import { multiply } from "./math.ts";

import { subtract } from "./math.ts";

export function calculate(a: number, b: number): number {

return subtract(multiply(a, 2), b);

}

// This export is never used - bundler will tree-shake it

export function unusedHelper() {

return "never called";

}

// math.ts

export function add(a: number, b: number): number {

return a + b;

}

export function subtract(a: number, b: number): number {

return a - b;

}

export function multiply(a: number, b: number): number {

return a * b;

}

// Unused export - will be removed

export function divide(a: number, b: number): number {

return a / b;

}

// logger.ts

export const logger = {

info: (msg: string) => console.log(`[INFO] ${msg}`),

error: (msg: string) => console.error(`[ERROR] ${msg}`)

};

// Unused export

export const debugLogger = {

log: (msg: string) => console.debug(msg)

};

// types.ts

export interface Config {

debug: boolean;

timeout?: number;

}

export type Status = "idle" | "loading" | "error";

this example shows several bundler nuances. the bundler analyzes the dependency graph: index.ts → utils.ts → math.ts, plus logger.ts and type-only imports from types.ts.

notice what happens:

- tree-shaking:

unusedHelper(),divide(), anddebugLoggerare never imported, so they're stripped from the bundle - type stripping: the

Configtype andtypes.tsimport are removed entirely—types don't exist at runtime - selective imports: only

multiplyandsubtractfrommath.tsare bundled, notaddordivide - re-exports:

calculatefromutils.tsis included because it's used inindex.ts

the bundled output would look like this:

// bundle.js

(function() {

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

function subtract(a, b) {

return a - b;

}

function calculate(a, b) {

return subtract(multiply(a, 2), b);

}

const logger = {

info: (msg) => console.log(`[INFO] ${msg}`),

error: (msg) => console.error(`[ERROR] ${msg}`)

};

const config = { debug: true };

const result = calculate(10, 5);

logger.info(`Result: ${result}`);

})();

notice how add(), divide(), unusedHelper(), debugLogger, and all type definitions are gone. the bundler only includes what's actually used, creating a smaller, optimized bundle.

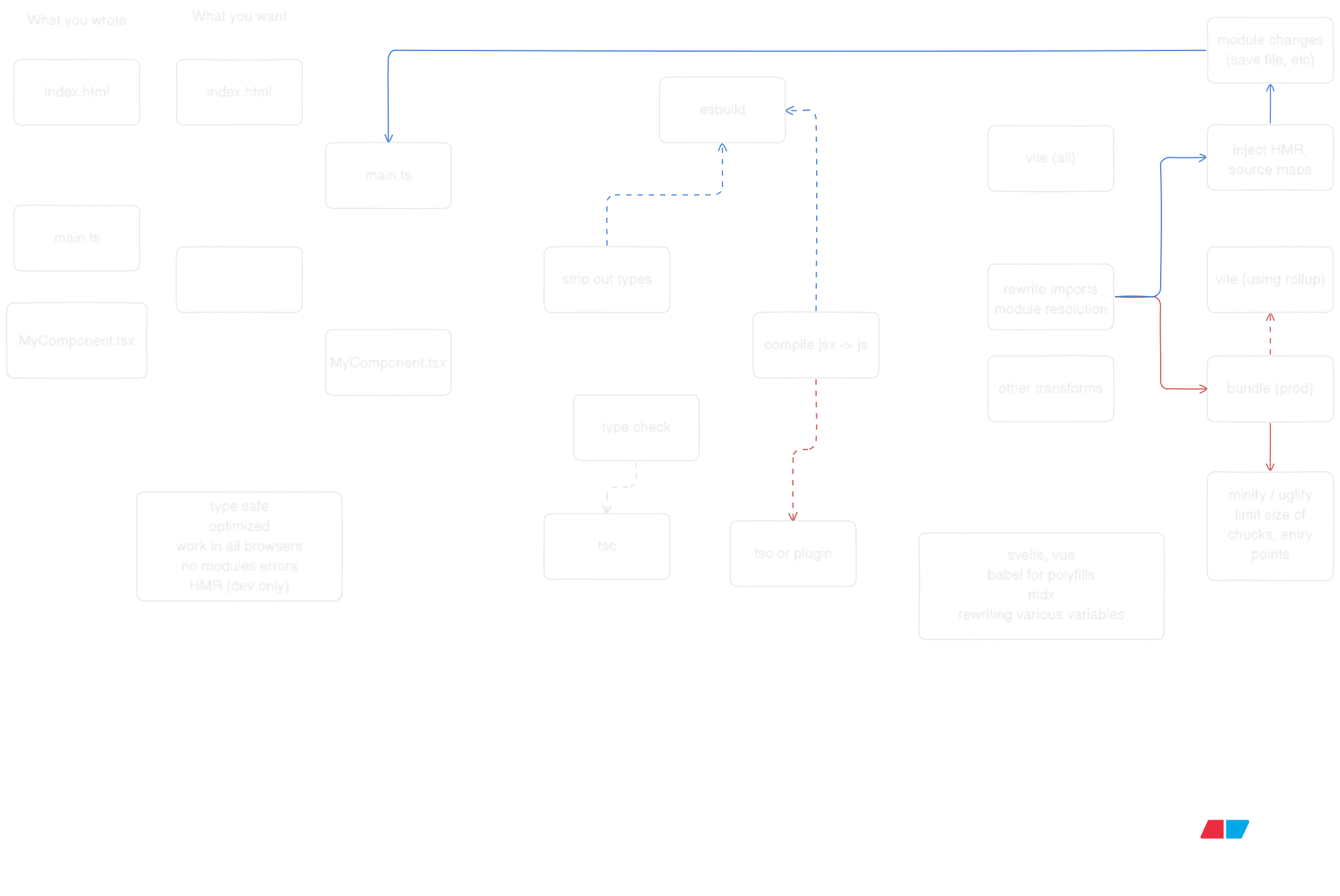

bundlers are magical and powerful tools , and mostly they are not something you need to worry about , but if you are curious about how they work , check out the diagram of vite works.

follow the work of Evan You and

Jared Palmer to learn more about how bundlers work.

- Learn more about [Vite]

- Explore [esbuild]

- Check out [RSPack]

- Discover [Rollup]

- Dive into [Webpack]

- Try [Parcel]

- Learn [Next.js]

Since we are no longer limited by javascript in both the frontend and backend, we can now build scalable and performant systems with a single language. But the real magic happens when you start connecting these pieces together—when your frontend can call your backend with full type safety, when your database queries are validated at compile time, and when your server actions feel like local function calls.

Type-Safe APIs: tRPC

Remember when API calls meant writing fetch requests, hoping your types matched, and debugging runtime errors? Alex / KATT built [tRPC] to solve exactly that. With tRPC, your backend procedures become type-safe functions that your frontend can call directly.

// server/router.ts

import { initTRPC } from '@trpc/server';

import { z } from 'zod';

const t = initTRPC.create();

export const router = t.router({

getUser: t.procedure

.input(z.object({ id: z.string() }))

.query(async ({ input }) => {

// This runs on the server

return { id: input.id, name: 'Aryan', email: 'aryan@example.com' };

}),

createPost: t.procedure

.input(z.object({ title: z.string(), content: z.string() }))

.mutation(async ({ input }) => {

// Save to database, return result

return { id: '123', ...input };

}),

});

// client.tsx

import { createTRPCReact } from '@trpc/react-query';

import type { AppRouter } from './server/router';

const trpc = createTRPCReact<AppRouter>();

function Component() {

// Fully typed! TypeScript knows the return type

const { data } = trpc.getUser.useQuery({ id: '1' });

const createPost = trpc.createPost.useMutation();

return (

<div>

<p>{data?.name}</p>

<button onClick={() => createPost.mutate({

title: 'Hello',

content: 'World'

})}>

Create Post

</button>

</div>

);

}

No more any types. No more guessing what the API returns. The types flow from your backend to your frontend automatically. If you change the backend schema, TypeScript will catch the mismatch before you even run the code.

Server Actions: Functions That Live on the Server

Next.js took this idea even further with Server Actions. Instead of creating API routes, you just write async functions. They run on the server, but you call them from your React components like regular functions.

// app/actions.ts

'use server';

import { revalidatePath } from 'next/cache';

import { z } from 'zod';

const createPostSchema = z.object({

title: z.string().min(1),

content: z.string().min(10),

});

export async function createPost(formData: FormData) {

// This runs on the server, always

const rawData = {

title: formData.get('title'),

content: formData.get('content'),

};

const validated = createPostSchema.parse(rawData);

// Save to database

const post = await db.post.create({ data: validated });

// Revalidate the page cache

revalidatePath('/posts');

return { success: true, id: post.id };

}

// app/page.tsx

import { createPost } from './actions';

export default function Page() {

async function handleSubmit(formData: FormData) {

'use server'; // This can also be inline

await createPost(formData);

}

return (

<form action={handleSubmit}>

<input name="title" />

<textarea name="content" />

<button type="submit">Create Post</button>

</form>

);

}

The form submission happens on the server. No API route needed. No fetch call. Just a function call that happens to execute on a different machine. Next.js handles the serialization, the network call, and the response—all transparently.

Database Connections: Type Safety All the Way Down

But what about the database? You can't just write SQL strings and hope for the best. That's where tools like [Prisma] and [Drizzle] come in. They turn your database schema into TypeScript types.

// schema.prisma (Prisma)

model Post {

id String @id @default(cuid())

title String

content String

published Boolean @default(false)

createdAt DateTime @default(now())

author User @relation(fields: [authorId], references: [id])

authorId String

}

model User {

id String @id @default(cuid())

name String

email String @unique

posts Post[]

}

// Using Prisma

import { PrismaClient } from '@prisma/client';

const prisma = new PrismaClient();

// Fully typed! TypeScript knows the return shape

const post = await prisma.post.create({

data: {

title: 'My Post',

content: 'Hello world',

author: {

connect: { email: 'aryan@example.com' }

}

},

include: { author: true }

});

// TypeScript knows post.author exists and is a User

console.log(post.author.name);

Or with Drizzle, you define your schema in TypeScript:

// schema.ts (Drizzle)

import { pgTable, text, boolean, timestamp } from 'drizzle-orm/pg-core';

export const posts = pgTable('posts', {

id: text('id').primaryKey(),

title: text('title').notNull(),

content: text('content').notNull(),

published: boolean('published').default(false),

createdAt: timestamp('created_at').defaultNow(),

});

export type Post = typeof posts.$inferSelect;

export type NewPost = typeof posts.$inferInsert;

// Using Drizzle

import { db } from './db';

import { posts } from './schema';

// TypeScript infers the return type from your schema

const allPosts = await db.select().from(posts);

// allPosts is Post[]

const newPost = await db.insert(posts).values({

id: '123',

title: 'Hello',

content: 'World',

}).returning();

// newPost is Post[]

Your database becomes a typed API. Change the schema, regenerate the types, and TypeScript will show you every place in your code that needs updating.

Putting It All Together

Here's what it looks like when everything connects:

// 1. Database schema (Prisma)

model Post {

id String @id

title String

content String

}

// 2. Server Action

'use server';

import { prisma } from './db';

export async function createPost(data: { title: string; content: string }) {

return await prisma.post.create({ data });

}

// 3. React Component

import { createPost } from './actions';

export default function Page() {

async function handleSubmit(formData: FormData) {

'use server';

await createPost({

title: formData.get('title') as string,

content: formData.get('content') as string,

});

}

return <form action={handleSubmit}>...</form>;

}

Or with tRPC:

// 1. Database (Drizzle schema)

export const posts = pgTable('posts', { ... });

// 2. tRPC Router

export const router = t.router({

createPost: t.procedure

.input(z.object({ title: z.string(), content: z.string() }))

.mutation(async ({ input }) => {

return await db.insert(posts).values(input).returning();

}),

});

// 3. React Component

const createPost = trpc.createPost.useMutation();

<button onClick={() => createPost.mutate({ title: '...', content: '...' })}>

Create

</button>

The types flow from your database schema → your server code → your frontend. One language, one type system, end-to-end type safety. No runtime surprises. No API mismatches. Just code that works.

Effects: Where Errors, Concurrency, and Observability Live in Types

But here's the thing: even with all this type safety, you still have to deal with the messy reality of building systems. What happens when the database connection fails? What if your API call times out? How do you handle retries, cancellation, and resource cleanup? Traditional JavaScript throws errors, returns null, or just crashes. Michael Arnaldi and the team at [Effect] built something different: a language for effectful computations where errors, concurrency, and observability are first-class citizens in your type system.

Effect treats side effects—database calls, HTTP requests, file I/O—as typed values. Instead of async function fetchUser(), you get Effect<User, DatabaseError>. The type tells you exactly what can go wrong, and TypeScript forces you to handle it.

import { Effect } from 'effect';

// Traditional approach: errors are invisible

async function fetchUser(id: string): Promise<User | null> {

// What if the database is down? What if the query times out?

// The type doesn't tell you, so you forget to handle it

return await db.user.findUnique({ where: { id } });

}

// Effect approach: errors are in the type

function fetchUser(id: string): Effect.Effect<User, DatabaseError | NotFoundError> {

return Effect.gen(function* (_) {

const user = yield* _(db.user.findUnique({ where: { id } }));

if (!user) {

return yield* _(Effect.fail(new NotFoundError(`User ${id} not found`)));

}

return user;

});

}

Now TypeScript knows that fetchUser can fail with DatabaseError or NotFoundError. You can't ignore it. You have to handle it, and Effect gives you tools to do it elegantly:

import { Effect, pipe } from 'effect';

// Retry with exponential backoff

const userWithRetry = pipe(

fetchUser('123'),

Effect.retry({

times: 3,

delay: 'exponential',

})

);

// Fallback to default user

const userWithFallback = pipe(

fetchUser('123'),

Effect.catchAll(() => Effect.succeed(defaultUser))

);

// Timeout after 5 seconds

const userWithTimeout = pipe(

fetchUser('123'),

Effect.timeout('5 seconds')

);

But Effect goes deeper. It gives you structured concurrency—the ability to run multiple effects in parallel, cancel them when needed, and clean up resources automatically. Kit Langton created [Visual Effect] to help developers understand these concepts through interactive examples. The idea is simple: when you start a database transaction, you want to make sure it closes, even if an error happens. Effect makes that automatic.

import { Effect, Context } from 'effect';

// Define a database service

class Database extends Context.Tag('Database')<Database, {

query: (sql: string) => Effect.Effect<unknown, DatabaseError>;

close: () => Effect.Effect<void>;

}>() {}

// Acquire resource, use it, release it automatically

const program = Effect.gen(function* (_) {

const db = yield* _(Database);

// This runs in a transaction

const users = yield* _(db.query('SELECT * FROM users'));

// If anything fails, the connection is automatically closed

return users;

}).pipe(

Effect.scoped // Automatically manages resource lifecycle

);

, Domains Lead at Vercel, shared how they integrated Effect into their Domains platform. The superpowers? Error handling that's impossible to forget, observability built into every operation, and tests that don't require mocking—you can swap implementations at the type level.

// In production: real database

const production = Layer.succeed(Database, realDatabase);

// In tests: in-memory database

const test = Layer.succeed(Database, inMemoryDatabase);

// Same code, different implementations

const program = pipe(

fetchUser('123'),

Effect.provide(process.env.NODE_ENV === 'test' ? test : production)

);

Ethan Niser has been advocating for Effect on the frontend, showing how it's not just a backend tool. The same error handling, the same resource management, the same composability—but in your React components.

// app/components/UserProfile.tsx

import { Effect } from 'effect';

import { use } from 'react';

function UserProfile({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

// Effect works with React's use() hook

const user = use(

pipe(

fetchUser(userId),

Effect.catchAll((error) => {

console.error('Failed to fetch user:', error);

return Effect.succeed(null);

})

)

);

if (!user) return <div>User not found</div>;

return <div>{user.name}</div>;

}

Effect is what happens when you take functional programming seriously in TypeScript. It's not just about avoiding null or handling errors—it's about making your entire system's behavior explicit in types. Retries, timeouts, cancellation, resource cleanup, observability—all of it becomes part of your type signature, and TypeScript makes sure you handle it correctly.

This is the future of web development, and it's here to stay. JavaScript started as a 10-day hack, became the language of the browser, conquered the server, and now it's creating systems where the boundaries between frontend, backend, and database start to dissolve. The same language, the same types, the same mental model—from the database to the user's screen. And with Effect, even the messy parts—errors, concurrency, resources—become first-class citizens in your type system.

Not bad for a 10-day hack.

fin.